|

The U.S.S.R. pavilion being built on Île Notre Dame. Behind it, the Steel Pavilion has been built. But Critical Path is enabling Churchill's people to prevent little gaffes from becoming big blunders. As the weekly progress reports pour in, the CPM charts are consulted, and computers programmed with all the basics keep track of what's on time and what isn't. Even the briefing-room sessions are proving useful. They keep people on their toes and help them avoid working at cross purposes. More to the point, people are finding that those impossible deadlines aren't impossible after all. Even the crazy-sounding orders from The Colonel's office somehow work out. Such as his idea of landscaping while building construction is still going on. "We just can't wait to do things in the ordinary or logical sequence," explains Gilles Sarault, a deputy who is also Churchill's chief engineer. Or, as The Colonel himself puts it: "Virtually nothing in Expo relates to normal conditions." (Later he admits his Expo job is a lot tougher than building 192 airfields in wartime.) As bridges span the river, roads get laid and buildings begin to rise -- nearly always on schedule at every stage -- the fear and suspicion Colonel Churchill has aroused initially begin to give way, first to respect, then to an admiration approaching awe. Far from the Blimpish empire-builder many had supposed him to be, Ed Churchill is proving himself the mover of the action -- a cutter of red tape, a foiler of bureaucrats. At times he virtually lays his job on the line by going ahead on his own on some move that theoretically has to have prior approval from Expo's directors. It isn't that those first impressions of him are entirely false; but there's a great deal more to the man. Most associates still agree, for instance, that he's a hot-tempered, impatient bully. "But," says Pierre de Bellefeuille, director of exhibits, "to a certain extent he puts on this rough attitude. It gets results." As it becomes clear that he means what he says about building Expo on time, even if he can say it only in English, the French-language newspapers are won over to his side. Even underlings he has tongue-lashed testify that he's scrupulously fair. "It's always an impersonal thing with The Colonel," says one, "and 10 minutes after he has blown up, he'll go on with his business as if he's forgotten all about it." "He packs 5,000,000 things in his mind -- and remembers" Not that The Colonel ever really forgets anything that might be usefully remembered. "I've been embarrassed at times to discover he knows more about my job than I do, right down to some trivial detail," says Norman Hay, head of the design division within Installations. "He has an uncanny ability to pack five million things into his mind -- and remember them all," says Gilles Sarault, the chief engineer. Charlie Gahagan, head of Project Control, is startled to discover that fact during a rare social moment with The Colonel, at a cocktail party. "I wonder," he says to The Colonel, "if you remember when we first met." He's thinking back nearly five years, to a pretty casual social encounter that couldn't have meant much to The Colonel then or since. "Sure I remember," The Colonel snaps back, "and the bar bill was $22." The Colonel puts his mastery of detail to good use in problem-solving. "He amazes everyone," says Gaston Lambert, Churchill's assistant. "After all, he can't be an expert on everything, yet he will listen to a problem in some field he hardly knows, then make a decision, and everyone will agree it's the right decision. They don't know how he does it." But there is one other facet of Churchill's characters that remains most amazing to the people around him: Here he is, an army engineer who belongs to the generation that gave engineers their reputation as practical, hard-nosed bridge-builders who'd be insulted if you said their work was artistically appealing. Yet here he is, demonstrating an aesthetic sense that would do credit to an art-museum curator. "He's a pretty rare type," says Pierre de Bellefeuille, "a completely competent construction man who has a thorough grasp of the cultural things we're trying to do." Churchill is tough on designers who'd go on redesigning their own works forever if somebody let them; but people who expect to hear him urging designers to sacrifice aesthetics for expedience are startled by his passionate defence of the artist. "Every time we have not accepted the best aesthetic device," Churchill says, "we have been wrong." |

|

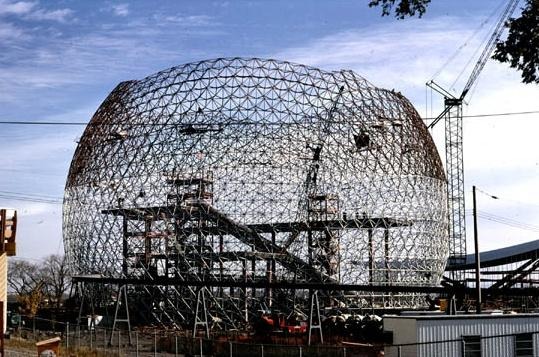

The U.S.A. pavilion being built on Île Sainte Hélène Yet somehow, more often than not, The Colonel finds ways of combining aesthetics and expedience, and reactions from Operations people -- the ones who actually run the show -- now range typically from gratitude to delight. Ann Farris, who must supervise handling of all props and costumes for World Festival performers in six locations around Montreal (the Bolshoi Opera alone is bringing 28 baggage cars of scenery) remembers wringing her hands because Expo Theatre was nothing but a set of blueprints only 14 months ago. Now, still amazed, she says, "The Colonel said it would be ready on time and, by God, it was!" "Without Critical Path," says Peter Kohl, supervisor of a concessions setup that includes 70 restaurants, 72 snack bars and 600 other shops, " I wouldn't have known when I was going to be able to take over any building." As for The Colonel, now almost a legend around Expo: "He's one of the few men where the man measures up to the myth." Today, among visitors who see Expo 67 as an artistic triumph, the people most impressed are those who remember that the whole show was created in about three and a half years -- half the time it took to create smaller, less-appealing world's fairs of the past. To describe this achievement, they use such adjectives as incredible, monumental and even miraculous. But insiders who saw Expo get built will tell you that the appropriate word is Churchillian. Copyright © by Maclean's magazine, June 1967 edition, all rights reserved. Notice: The Expo 67 in Montreal website is located on a "non-commercial" ISP and is intended for historical and educational purposes only. 5/5

|