Expo 67: 40th Anniversary Celebrations Edition

October 1, 2007

Our Final Report...

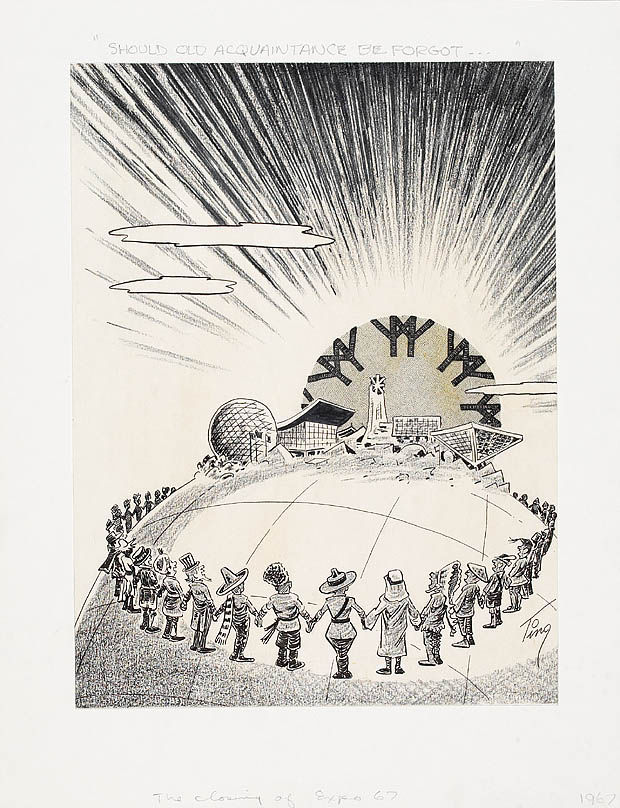

Photo credit: © the National Archives of Canada

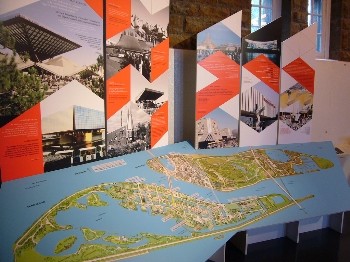

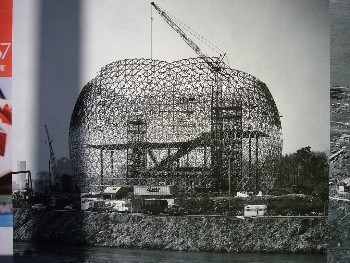

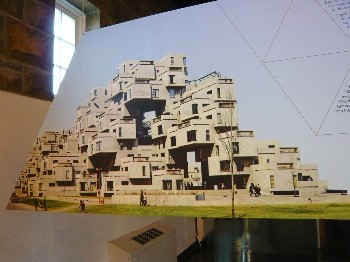

Montréal remembering Expo 67

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All photographs by Penfan Sun, "Montréal Museum of Fine Arts" except for the "Man and His World" foliage symbol by Kayo Shibano, "City of Montréal" building. |

|

|

--------------------------------------------------------- |

|||

Movies at Expo Where's it all happening this year? In film, baby by Wendy Michener EXPO 67 is a many-screened splendor. Everywhere you look there are movies, movies, movies. The whole site is a mass of reflecting surfaces, flashing lights and refracted images. In the Cuban Pavilion projectors hang from the ceiling and beam newsreels of the revolution onto outdoor screens. In the Czech Pavilion slides are thrown onto moving plastic blocks while film loops play on twirling silver balls or shine through glasses darkly. In Quebec's pavilion hidden projectors send out 16-mm messages about furs, forests, water and textiles onto surfaces thrust out towards you in tubes and cubes. In the British tower Sean Kenny kaleidoscopes 1,000 years of history into a craggy montage of sound and film. World's fairs in general are a chance for artists to experiment at someone else's expense. In the past the major experimenting was in the fields of design and architecture. There's lots of that at Expo, too, but this time cinema really comes into its own. There's no avoiding the great visual onslaught. It might just as well have been an experimental film festival as a world's fair. Canada alone is responsible for the production of a dozen major film projects costing, at a conservative estimate, about $6 million. No one will ever guess from these exhibits that we have no true film industry. Film is an obvious choice when it comes to international exhibits. It helps to get around that prickly language problem. Besides, movies are so securely linked with the idea of pleasure that people will stand in line for hours to see one. The success of the Magic Lantern at the Brussels World's Fair and of the Thompson-Hammid film at the New York fair proved just how much a good popular film can do to bring out people into a pavilion. So it's not surprising that almost everyone who can afford a film has got one, and most have followed the lead of these two hits into multi-screen or multi-image or at the very least multi-slide shows. The Telephone Pavilion, for instance, features a nine-screen circular travelogue. The public is drawn in for a free show and exits smack into the middle of a nice big telephone display. The Expo people like to say that movies will never be the same again. That's true of course. But movies are not the same already. Splitscreen and multi-image has invaded not just the world of avant-garde films (notably Andy Worhol's Chelsea Girls) but has also been used to spectacular effect in the big commercial racing movie Grand Prix. What could be more appropriate to express our mixed-up modern times than multi-media and the fragmented image? Speed, simultaneity and diversity are basic to the urban way of life. One screen doesn't give enough information fast enough anymore. We want more than one story on the front page of our newspapers, and we are ready to absorb two or three moving pictures at once. Soon, who knows, we may be demanding multi-screen television. Still there's no doubt that all the goings on at Expo will speed up the film revolution that is already underway. In a sense Grand Prix was made possible by the New York World's Fair and several of the subsidized experiments at Expo open up more possibilities. Canada is responsible for the greatest number of experimental films and also for the single most ambitious, most accomplished project: Labyrinth. Briefly, Labyrinth is a three-chamber film that attempts to re-create every man's discovery of himself in his lifetime. There are slicker multi-screen films at the fair, there are equally inventive combinations of architecture and exhibit, and there are sound-and-light shows that are much more economically produced. But no other experiment is pushed so far, or tries to express so much. Labyrinth is like no other film I've ever seen. The idea is novel enough, but the most remarkable achievement of Roman Kroitor, Colin Low and Hugh O'Connor is to have a very intimate picture entirely out of documentary footage. It is almost impossible to make real drama out of the general case, but somehow they have used the magic of multi-screen to turn circuses, crocodile hunts, boxing matches, ancient temples and a thresherman's ball into personal matters affecting us all. It's a thing of beauty. Chris Chapman, the creator of an exhilarating Ontario film -- A Place To Stand -- has his Hollywood lab technicians talking about Academy Awards as they struggle to make his film. The irony of this scene is that in Hollywood terms Chapman is practically an amateur, not being a union cameraman. Working in his country house outside Toronto on a blackboard divided into one-inch squares, Chapman painstakingly traced out the paths of as many as fifteen different images moving around within the overall screen area. Then he worked out the exact position of each separate moving picture with the help of a small computer and sent off huge editing charts and elaborate instructions to Hollywood. Right now that lab is busy working out a simpler way to print this style of film because they think the technique is sure to catch on. Ontario spent more than $300,000 on this film -- a huge sum for a risky undertaking. The gamble has certainly paid off. Graeme Ferguson's documentary, Polar Life, with its rotating eleven-screen theatre may not spawn any immediate imitations, but it proves to my mind that multi-screen is more than a gimmick. (They said that the talkies wouldn't last either.) There's no single-screen process which could do equal justice to the icy vastness of the North, or match the haunting effect of three-story-high faces staring out at you. At the very least all these movie experiments have accomplished one thing already: they've taught our film makers how to cut down on words and so make effortlessly bilingual movies. This in turn might just lead to some of that understanding and consolidation that everyone's talking about. © by Maclean's Magazine, June 1967. All rights reserved.

Expo 67 website editorial: Several years ago I contacted Les Lawrence, husband to the late Wendy Michener. I asked Les to write up a short biography about Wendy regarding another excellent article that she wrote for Maclean's which appears on a different website that I do research for. Presented here then, is the biography that Les wrote... WENDY MICHENER, critic, arts journalist and broadcaster, was a lively and perceptive writer on film, dance and culture until her unexpected death in 1969 at the age of 34. As a columnist and freelance writer, her reviews and feature articles appeared in the Montreal Herald, the Toronto Star and the Globe and Mail, Saturday Night, and Maclean's magazine. During her brief career, Wendy Michener also worked as a producer for CBC Radio, produced several hour long films on the movies, and at the time of her death was at work on a film with artist and filmmaker Joyce Weiland. Fluently bilingual, she was, in the words of one critic "our first national critic, because she could speak for both our cultures." A Wendy Michener Symposium takes place annually at York University sponsored by the Wendy Michener Memorial Fund, instituted by the late Right Honourable Roland Michener and Mrs. Norah Michener in memory of their daughter. Related links: The Michener Awards Foundation "At Expo 67, Montréal became a laboratory from which would emerge a whole new way to see movies on the big screen. Nearly 40 years later, the city remains the hub of the giant-screen format, a vibrant one-stop-shop where talent and creativity sizzle – and the resulting products dazzle. The following pages offer a glimpse of a Montréal industry whose wide array of services, from pre-to postproduction, continue to attract, assist and amaze foreign giant screen productions from all over the world." - Rock Pinard, Editor, Spotlight. Click here for the report in PDF format: The Giant Screen Industry in Montréal . The document contains information on how the movie (in Chamber One) at the Labyrinth pavilion became the catalyst for future IMAX technology. Our final Expo 67 tribute continues on the next page... |

1/8