"Man and His World International Fine Arts Exhibition Expo 67 Montréal Canada" by Pierre Dupuy © the Canadian Corporation for the 1967 World Exhibition and the National Gallery of Canada

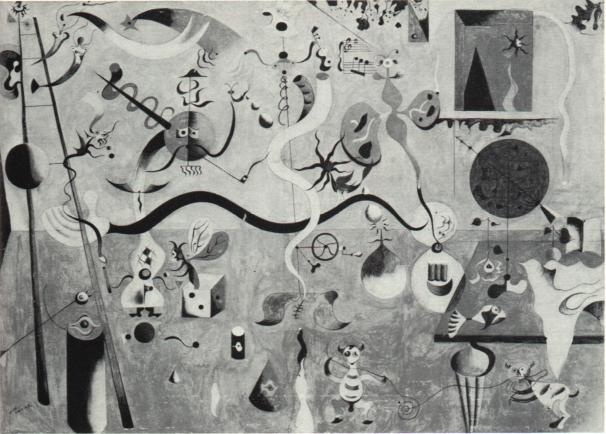

| Joan Miró. 1893-

Harlequin's Carnival. 1924-5 The Harlequin's Carnival of 1924-5 was the culminating work in a series of major paintings by Joan Miró which were devoted to more and more fanciful, cryptographic improvisations on the same theme of his native Catalan landscape. The first great achievement in the series was The Farm of 1921 which was owned by Ernest Hemingway and inconspicuously incorporated elements of a Synthetic and a basically realist Cubist style. This influence was partly derived from Miró friend and fellow Spaniard, Pablo Picasso, whom he had recently met in Paris after acquiring an academic training and passing through Impressionist and Fauve influence phases in Spain. In style, Carnival still owes much to the flat surfaces, random compositions, linear rhythms and "made" space of the Cubist collage, since the whole effect is of a children's playroom, cluttered with all sorts of animals, toys and musical instruments. These subject-objects are conceived uniformly as paper cut-outs so that distinctions between the real and imaginary, the organic and inorganic completely break down. This profusion of contrasting elements results, not in chaos, but in an easily readable pictorial structure. As in the sculpture of his friend, Hans Arp, the so-called biomorphic element combines with that of abstract calligraphy to heighten the viewer's appreciation of both. Both the highly personal style and the imagery of Miró, moreover, were in keeping with the theories of French Surrealism, a movement which was founded during the very year in which this painting was begun. With the emphasis placed by Surrealism upon automatic creation from the unconscious mind, it was natural that highly divergent personal styles would develop. It is characteristic of Surrealist art, in contrast to the Cubist and abstract tradition which have tended to stress a common, even an impersonal approach, that style is seen as a kind of personal handwriting of the artist rather than as an exalted and independent aesthetic goal. It is consequently in the realm of content that Surrealism expected to find its common denominator and, indeed, that Miró participates directly in Surrealism. For, although the rich phantasmagoria of his dream-carnival is not rendered in the magic-realist technique common to such Surrealist painters as Magritte, Dali or Tanguy, his imagery does not include enough sexual fetishes to betray the Surrealist interest in Freudian psychology, which his friendship with the American, Henry Miller, doubtless intensified. None the less, Miró's erotic allusions appear discreet indeed, when compared with the comically obscene ribaldry of Miller or of those French Surrealist writers who, in their iconoclastic wish to attach the idea of art as a humanist discipline, described the creative act in art as a form of copulation. In Harlequin's Carnival, the decorative fabric of the composition and the sense of a world at play emphasize instead the carnival theme itself recalling the seventeenth-century Dutch tavern scenes of Jan Steen, which in 1928 would provide the point of departure for one of several "Dutch interiors" done by Miró after a trip to the Netherlands. |